Water Poverty

Understanding the problems with access to water and poverty in the Brussels-Capital Region

Poverty

Social action

Policy planning

In 2018, water access was cut off at 1200 families in the Brussels-Capital Region. In 2009 this was the case with 98 families. This explosion of closures and the rise in poverty rates have made the regional public services decide to tackle the phenomenon of “water poverty”. In addition, the government of the Brussels-Capital Region reiterated that access to water is a fundamental right and that cutting off access to water is a violation of this. In collaboration with Sia Partners, Méthos brought together public and social actors to develop concrete and social solutions.

The results and figures of many of the studies on this topic do not take into account the individual living situations of people and are therefore insufficient to understand the phenomenon of water poverty. Why are people in a situation of water poverty in a city like Brussels? Which events can lead to the closure of water access? What are the main problems? Who are the people in water poverty? What difficulties do they face first? Only when we have formulated a clear answer to the above questions, it becomes possible to think about adapted solutions. This is what our ethnographic research was all about: conducting fieldwork with people who are in a situation of water poverty.

Our research focuses on the experience of families in water poverty in different communes of the Brussels Region. During extensive in-depth interviews with families, at their homes, we captured their stories of living in (water) poverty.

It was a night during winter. We came back home around 7pm to find out there was no electricity and no water in our house. I was with my 4 kids.

Systemic poverty

The phenomenon of water poverty is seldomly an isolated fact. Families experience water poverty as part of a larger poverty story. They are often in situations of (serious) debt and have a hard time controlling their spending. The majority of the families rent their accomodation. They pay exuberant amounts for gas, electricity and water as the houses they rent are poorly insulated, with hidden defects and leaks. Most families cannot deal with these high costs, but neither can they move because of their financial vulnerability. Little to no initiative comes from homeowners to renovate their properties.

When we don’t see a solution, problems weigh even more.

Their priority: securing tomorrow

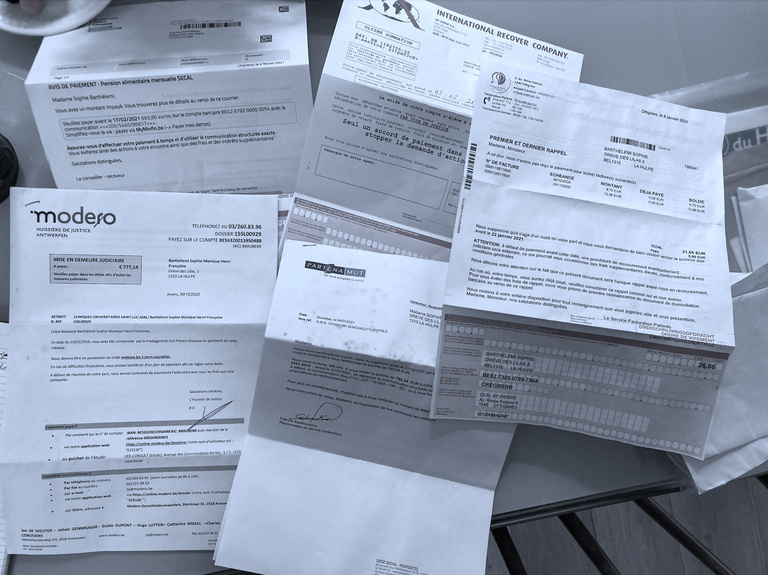

For these families, financial considerations about what can and cannot be paid are a constant concern: which bill should be paid first? What bill can I put aside, if only for a while? With a low income at their disposal, they make the choice to secure their basic living conditions: a roof (there is the constant fear of ending up on the street), clothes for the children (the sense of responsibility towards the children is immense) and food (even if some only can afford rice and sugar water at the end of the month).

The invoices for water are sent one to three times a year and given the high amounts, these invoices are impossible to pay when experiencing great financial vulnerability. It is not uncommon for such invoices to be ignored or forgotten. It is a way of distancing oneself from a reality that one does not understand, cannot face or from which one cannot see a way out.

I couldn’t. I left it hanging. I have a drawer with lots of mail in it. I put everything in it.

New forms of precarity

The diversity of situations between the families is striking. In addition to people who find themselves in a situation of generational poverty, we also see people who previously had no significant difficulties (with studies, job, housing). Unexpected problems with health, divorce or layoffs led to a situation of poverty, which recently were reinforced by the Covid-19 pandemic.

The population affected by water poverty is far from homogeneous. It implies we urgently need to differentiate intervention methods and policies and adapt them to the situations in which families may find themselves.

This is not a position in which I am happy. It's difficult, I don't want to run after assistance services, I just want to do my job.

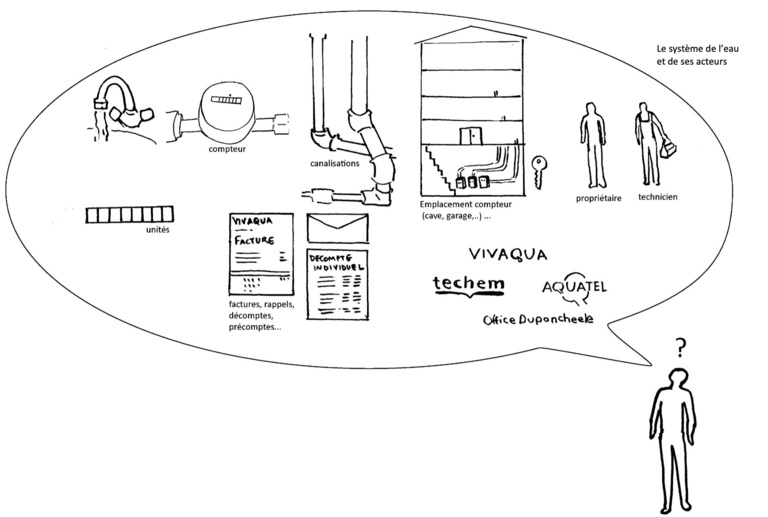

A complex system

Our work also allows to better understand the reasons for the “non-take up” of social benefits. This question is often asked by public authorities: why do so many families end up in court or in a situation where water is cut off, despite the existing social benefits? Why are so few families turning to existing welfare help (and thereby increasing the risk of sinking even deeper into poverty)?

Our study shows that often families only rely on themselves and how difficult it is for them to know who to turn to. Owners, property managers, technicians, the local welfare aid (CPAS-OCMW), the water supplier, other associations., … water and its administration form a complex infrastructural and administrative maze. Families in a precarious situation often experience this complexity when they are in an emergency situation, end up being alone and/or are without financial means. On top of that, they experience shame and guilt.

Recommen- dations

All research material and recommendations were discussed with a feedback committee consisting of water company Vivaqua, Brussels Environment, social welfare association (CPAS-OCMW) and various actors in the fight against poverty. Based on the results, this committee led by Méthos and Sia Partners has developed a series of actions and measures, including a list of priorities to be proposed to the government to combat the phenomenon of water poverty.

Read more

• The full report (FR)

References and biography

• Accès à l’eau, un droit pour tous? Paroles de naufragés, Mars 2018, FdSS & SocialEnergie

• De l’eau pour tous! Etat des lieux de la précarité hydrique en Belgique - 2019, Fondation Roi Baudouin

• Baromètre de la précarité énergétique et hydrique, Analyse et interprétation des résultats 2009-2018, Fondation Roi Baudoin, avril 2020

• Durabilité et pauvreté, Contribution au débat et à l’action politiques - Rapport Bisannuel 2018-2019, Service de lutte contre la pauvreté, la précarité et l’exclusion sociale

• (Re)cours toujours - Comprendre et combattre le non-recours aux droits pour lutter contre la précarité énergétique et hydrique, Centre d’Appui Social Energie, mars 2020

• Water affordability : Public operators’views and approaches on tackling water poverty, Aqua Publica Europea

• Measuring water affordability in developed economies. The added value of a needs-based approach, J. Vanhille and al.

• Etude sur les consommations résidentielles d’eau et d’énergie en Wallonie, AquaWal et CEHD, novembre 2015

A project in collaboration with Sia Partners.

Other projects

Energy-efficient housing

The standards for energy-efficient buildings are reshaping the way people live in them. The question, then, is how to factor people into the way new-generation buildings are designed and managed.

Energy-efficient homes are changing people’s lifestyles. On this project, Méthos worked with dwellers, housing organisations and authorities to integrate the human dimension more effectively in new construction standards.

• Download the abstract (fr / nl)

• Bruxelles Environnement

Participation in co-housing projects

An overview of best practices and the most effective ways of applying participatory methods to housing projects. What does participatory design involve? Why involve tenants in it? What strategies and tools work best? A study for the King Baudouin Foundation.

With a view to disseminating co-design philosophy, the King Baudouin Foundation asked Méthos to map out best practices and methods to foster participation in designing or renovating buildings.